At its core, debating relies on one simple premise. That is, there is a difference in the policy, principle or argument of the opposing speakers. This difference or ‘clash’ is explored throughout the debate, with the superiority of one speaker and their unique position being revealed.

Accordingly, it would be hard to call last night’s third and final leaders' forum a debate. All that was revealed was the lack of divergence between the political platforms on which Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott are running.

While the leaders dodged and postured to create a semblance of disparity, the debate affirmed the broad consensus that exists over the size of government, education, welfare, immigration and foreign policy in Australia.

The audience gained little from the time they invested in watching it

Like the first leaders' debate, the audience gained little from the time they invested in watching it.

This problem isn’t inherent in debates between politicians. The US Presidential Debates, as well as being watched by a much greater percentage of the population, have been able to distinguish candidates on broad ideological grounds.

The first debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney saw heated discussion about the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy. Mr Romney accused Mr Obama of pursuing an approach of “trickle down government”, while Mr Obama attacked Republican support of big business, pointedly asking “does Exxon Mobil need extra money?” These were debates that allowed voters to evaluate the two competing candidates and visions in front of them.

The key to winning government is therefore to win over the median vote

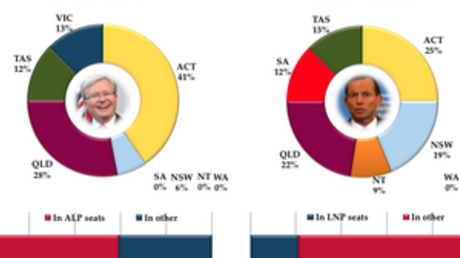

Of course, the American electorate is very different to that in Australia. Our relatively small population minimises the power of fringe and minority voices that are able to wield significant demographic power in parts of the US. Small single member electorates in the lower house further reduce the influence of geographically dispersed fringe parties that traditionally fare better in the Senate. The key to winning government is therefore to win over the median voter. Policy platforms converge to the centre, minimising the core differences between the candidates and parties hoping to win government.

The third leaders’ forum perfectly exemplified this convergence to the middle. Of the major issues discussed (aged care, education, budget surplus, immigration and foreign investment) there was negligible difference in the leaders’ positions. Given this, Mr Rudd and Mr Abbott spent the majority of the hour casting doubt on the ability of their opponent to deliver on promises or the subsidiary effects of either one being elected. The Prime Minister tried to sow uncertainty about the Coalition policy costings, while the Opposition Leader spent the night questioning the ability of a future Labor government to deliver on policy promises. This banter obscured the fact that the debate was now about the means rather than the end goal.

It was the opposition leader who benefited most from the narrowing of the debate. Mr Rudd was constrained in the number of Coalition programs that he could attack because many were similar to or derivative of those of his government. Forced to attack on issues of budgeting and transparency, the audience was more likely to accept Mr Abbott’s concluding characterisation that the PM had brought nothing more than a scare campaign to the debate.

Moreover, there was much more material for Mr Abbott to use in his own attacks against Mr Rudd than could be used against him. The six-year track record of Prime Minister is much better used as evidence of inept leadership than the actions of an Opposition leader.

Nonetheless, the leaders had to distinguish their policy platforms despite the limited political spectrum in which the debate was taking place. Mostly, this meant playing up the small differences that do exist: both leaders returned to the NBN and paid parental leave as if they were the only issues of the election. Mr Rudd, when speaking on aged care (a traditionally bipartisan issue) attempted to differentiate by canvassing how the NBN would help the elderly. Problematically, He never explained why that was something mutually exclusive to Coalition internet policy. Mr Abbott, on the same issue, quickly moved his response to how minute differences in superannuation reform would benefit workers in the sector. Whether or not this was a specific to these workers was unclear.

Last night’s forum was indicative of the political space that both major parties now occupy. In the absence of major philosophical differences, a debate is never going to be particularly effective at informing the audience about competing ideas, because there are none. What results is superficial attempts by both speakers to distinguish using matters of small national significance. Perhaps, by allowing minor parties such as the Greens into the debate, the change that is needed might occur. Until then, election debates in this country will always be less interesting and less insightful than those in other democratic states.