Below is a summary of Dr McRae's'presentation at the Melbourne Law School on Monday April 14. A full wrap up of that event can be found here.

I spent most of the campaign period for the legislative election in East Java Electorate number 1, comprising Surabaya and Sidoarjo. It's a large electorate - Surabaya is Indonesia's second largest city - with 10 seats in the DPR up for grabs. It's also an electorate where change was expected, as President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s Democratic Party had done best there in 2009. Preliminary results suggest the Indonesian Democratic Party - Struggle (PDIP-P) may have done best this time with 3 to 4 seats, ahead of the National Awakening Party (PKB).

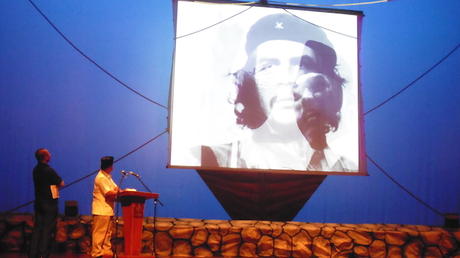

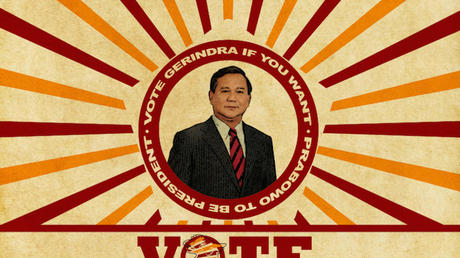

Party leaders and presidential candidates played a prominent role in the campaign in East Java. All the major parties brought their leading figures to East Java, whether to Electorate 1 or to nearby towns. Individual candidates also featured their party's prominent figures on their campaign posters, be it shaking their hand or looming over their shoulders - the poster pictured here is typical.

An exception was Golkar chairperson and presidential candidate Aburizal Bakrie. Bakrie did campaign in Surabaya, but he is unpopular locally because of the nearby Lapindo mud disaster, and Golkar candidates left him off their posters.

Indonesia’s multi-seat electorates push candidates from the same party to compete against each other - it's no good your party getting three seats if you are the fourth ranked candidate. A lot of local campaigning therefore wasn’t about party platforms or national figures. Rather candidates used local issues to gain attention, or positioned themselves as intermediaries between voters and government services while various incumbents reminded voters who had delivered local development projects. Some candidates promoted their party only when it suited them: a local observer told me one candidate's strategy was essentially to undermine his own party's incumbent by campaigning in the same spot as them the following day, as that would be sufficient for him to win a DPR seat.

Moving on to the national results and their implications for the presidential election, the headline results from the quick counts were the lesser than expected plurality for PDI-P, which I discuss here, and the more fragmented parliament, with ten parties expected to gain seats.

What are the implications for the presidential election? In short, although the fragmented parliament creates more possibilities for nominating coalitions, Jokowi remains the clear frontrunner. We didn't see evidence of unexpected support for his rivals such as Prabowo Subianto in the legislative election, and the possibility to form more coalitions doesn't in itself create new viable contenders to Jokowi.

The lower than expected support for PDI-P could affect the way Jokowi governs though, if elected. He may well have a less free hand to choose a vice president, and his party will face an increased temptation to form the same sort of "rainbow coalition" that has been ineffective for each of his predecessors.

The potential difficulties for Jokowi in pushing through an agenda aren't limited to other parties. He would be the first president in democratic Indonesia for whom we can't take for granted that his agenda and his party's are the same. PDI-P says it is well prepared to govern this time, whereas Jokowi will also have his own ideas on appointments and his agenda. The interplay between him and PDI-P is something we should watch closely if Jokowi does indeed become Indonesia’s next president.